VOICES, is a forum that highlights the expertise of those who make up and support the organization. WFPG members and partners are invited to submit blog posts on international affairs and foreign policy topics, women's leadership, and career advancement. Posts represent the reflections and personal views of members and guest bloggers and not those of their employers or of the WFPG. Interested in submitting a post? Guidelines | Membership

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Cost of Care

Ainab Rahman, WFPG Generation Equality Forum Youth Engagement Chair

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

As a recent graduate, you might be wondering how you’re going to enter the workforce and join a diverse team with many ages, backgrounds, and (let’s face it) comfort levels with technology. Now that you’ve landed the job, it’s time to think about what happens next. You need to consider what role you’d like to play in your new organization. There are a series of steps you can take to become an essential, invaluable member of the team who others will trust and want to work with.

Here are 10 tips for what to do and what not to do to succeed at your first job.

Do

-

Keep your eyes open. When you’re a new employee, you have a lot to learn. Stay alert and gather as much information as possible. You’re likely to learn fastest through osmosis.

-

Tend toward formality (at first). You should aim to be formal in your early professional interactions. This could mean anything from dress code to email etiquette. You may find your workplace is pretty casual, but still, you should demonstrate that you’re capable of professionalism.

-

Ask questions. Speak up quickly ifyou’re confused about a rule or assignment. Remember, a sign of maturity is recognizing your own limitations and knowing when to ask for help.

-

Be a team player. You want to be known as someone who will not only get the job done (and do it well), but is ready to go the extra mile. That means being aware of what’s happening across the organization, anticipating potential problems, and fulfilling a need without being asked. This is often what distinguishes a good employee from a great one.

-

Take initiative. You want others to recognize your ambition. When possible, pursue opportunities or projects—outside of those you’re tasked with—that interest you. This also signals to leadership that you're committed to professional growth and finding your passion.

Don’t

-

Get hung up on your mistakes. The most successful professionals are the most resilient; they recognize that failures, on any scale, are crucial to personal growth. When you make a mistake, it’s important to reflect on that experience and assess what you could have done differently. Ask for feedback on how to improve, then move on.

-

Talk before you listen. Rather than speak out of nervousness or habit, pause. You don’t have to fill every silence! Listen first and think carefully about what you want to say. Allow yourself the time to process what you’ve seen and heard and you’ll form smarter questions and observations.

-

Have a bad attitude. Enthusiasm is one of the most important qualities you can bring to the table. This includes accepting the fact that no task is beneath you. For example, at times you may be asked to get coffee or run an errand. Treat these assignments as a necessary part of the job that keep the team moving forward. Be the person that boosts morale by always maintaining a positive attitude and prove that you’re a team player.

-

Overshare. Resist the urge to tell your coworkers too much about your personal life and be careful not to overstep professional boundaries. Save those conversations for happy hours. Also, be mindful of who you connect with and what you post on social media.

-

Be late. Tardiness is noticed. One of the easiest ways to show you're committed to the job is to be on time (which means 5–10 minutes early!)

When you start your first job, one of your top priorities should be making yourself an asset to the team. Be the person that others can depend on—someone who invests the time needed to help the organization achieve its goals, accepts any task or additional responsibility, and importantly, someone who shows up with a positive attitude, always ready to contribute. If you establish this reputation for yourself, you’ll develop trust with leadership and bonds with your colleagues. It will be these connections that you leverage to secure your next job and advance your career.

Miriam Roday is a researcher at the Institute for Defense Analyses where she focuses on Russia, digital disinformation and Transatlantic security. She began her career at 19 in the U.S. Senate and has since held positions across the public and private sectors, including with NGOs, congressional committees, political campaigns, and research institutions.

Return to top

Like gender inequality, climate change is an issue that touches every person and corner of the planet. The overlap between issues of gender and climate are significant, as climate intervention frameworks often fail to consider the unique needs of women and girls. As long as women and girls remain underrepresented in all levels of all sectors related to climate justice, this will continue. One group of women that are especially marginalized from climate justice, despite having always been at the forefront of the movement, are Indigenous women. For example, in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam, the loss of customary self-governance, combined with a lack of access and representation in political institutions, has prevented indigenous women from participating in decision-making forums on climate change.

Zoila Dolores Piedra Guamán is a farmer and homemaker from Puculay, in the Azuay province. Image Source

|

Indigenous female leaders bring a critical perspective on combating the climate crisis. As stewards of the land and custodians of traditional knowledge, they challenge the Eurocentric, capitalist, and individualistic models of mainstream development and conservation. Philosophies such as Buen Vivir (“good living” in English), based on the practices of the Quechua, Shuar, Aymara and Guarani peoples, is rooted in the cultivation of a harmonious relationship between people and nature to ensure mutual care. To put it simply, when people take care of the planet, the planet takes care of them. According to Buen Vivir, the Earth is not—and never has been—a commodity from which humans can extract resources. By framing the land as an entity deserving of care and rights, indigenous communities have been able to exist sustainably for thousands of years.

The devotion to care is what drives the climate activism of many indigenous women. For many female indigenous climate activists, they have a shared struggle with Mother Earth—or the pachamama, as she’s often called in Latin America—due to the multifaceted oppression from patriarchal, colonial, and capitalist forces. The connection between women and the pachamama as a creator and caregiver often drives their work. This notion makes feminism and environmental activism inseparable for activist Lola Cabnal, of the Mayan Q'eqchí in Bolivia: “One thing complements the other. Just as we women can be mothers and breastfeed our children, so is our cosmo, our environment that feeds us and [nourishes us]. We call the planet, our Mother Earth, because it gives us food and drink.” In many cases, women are the last ones left standing defending the land. In the Ecuadorian Andes, women of the Nazari, Puculcay, Morasloma, Bayán, and Hornillos tribes have been the frontline defense against the desertification of the páramo ecosystem. The majority of men in the community have abandoned the barren land, leaving the women in the community to revitalize the landscape in addition to raising their families.

Promoting the leadership of indigenous women is central to ensuring the social impacts of climate change are holistically addressed. Indigenous communities are adversely impacted by the climate crisis. As a result of extractivist industries, such as mining, agri-business, and fossil fuels, indigenous women have higher rates of respiratory diseases, miscarriages, and birth defects. They are at greater risk of being displaced from their home. Particularly in Latin America, female environmental and indigenous activists are at extremely high risk of being the victims of threats, bullying, judicial harassment, illegal surveillance, forced disappearances, blackmail, sexual assault and murder by the state, corporations, or paramilitaries. If these unique risks are not addressed, we cannot achieve climate justice. Conversely, when indigenous women are properly resourced to lead sustainable development and conservation efforts, the whole community is uplifted. Through participating in the sustainable agriculture program, women of the páramo gained leadership skills and education; which in turn promoted greater economic autonomy, the self-confidence to combat gender stereotypes, and prevented sexual violence.

Indigo Stegner is a senior at the George Washington University, majoring in International Affairs and minoring in Spanish and Cross-Cultural Communication (Anthropology). She is a Research Assistant (and former intern) at WFPG and has led their research and outreach efforts related to the Generation Equality Forum.

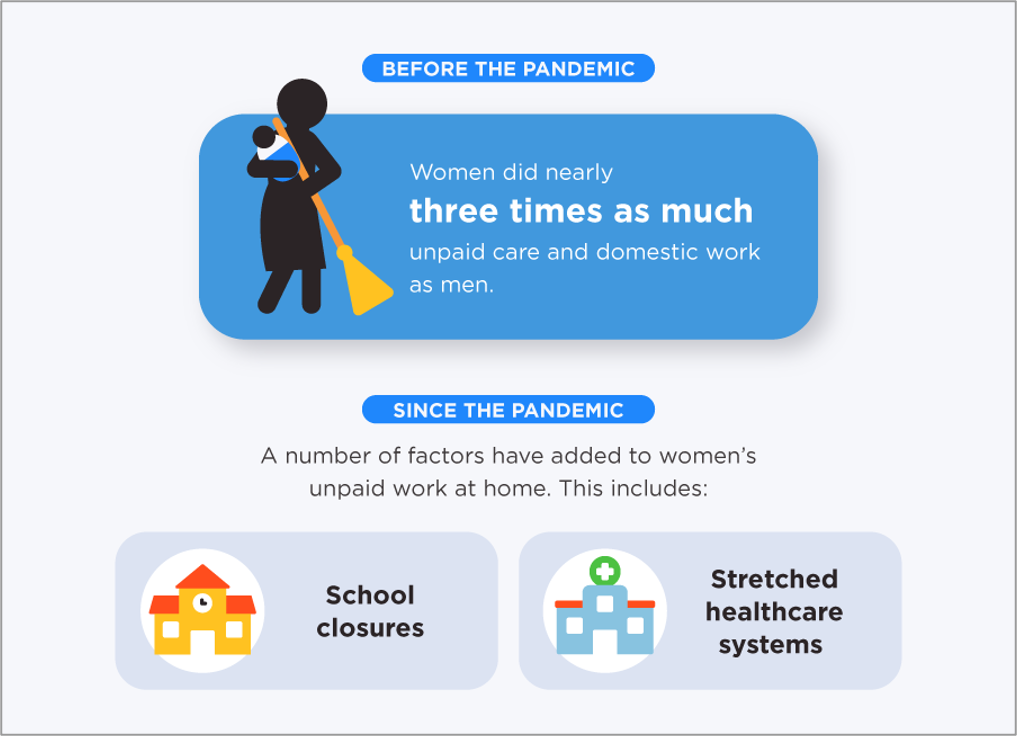

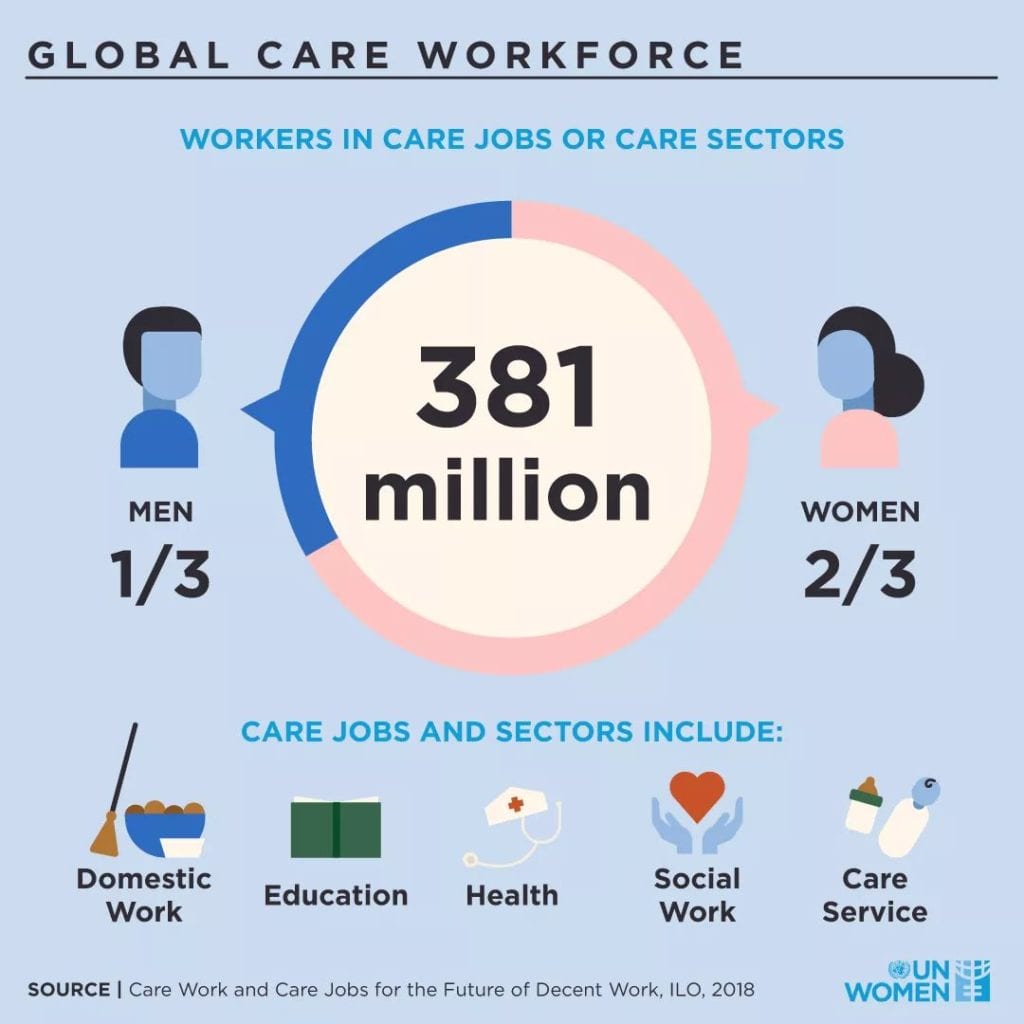

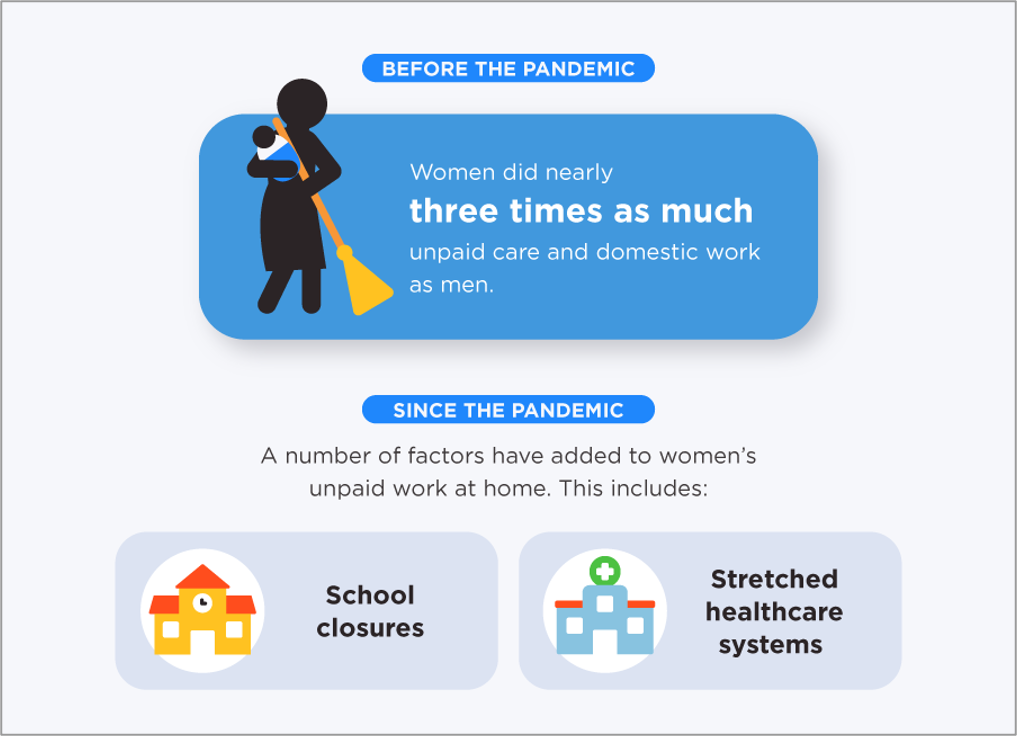

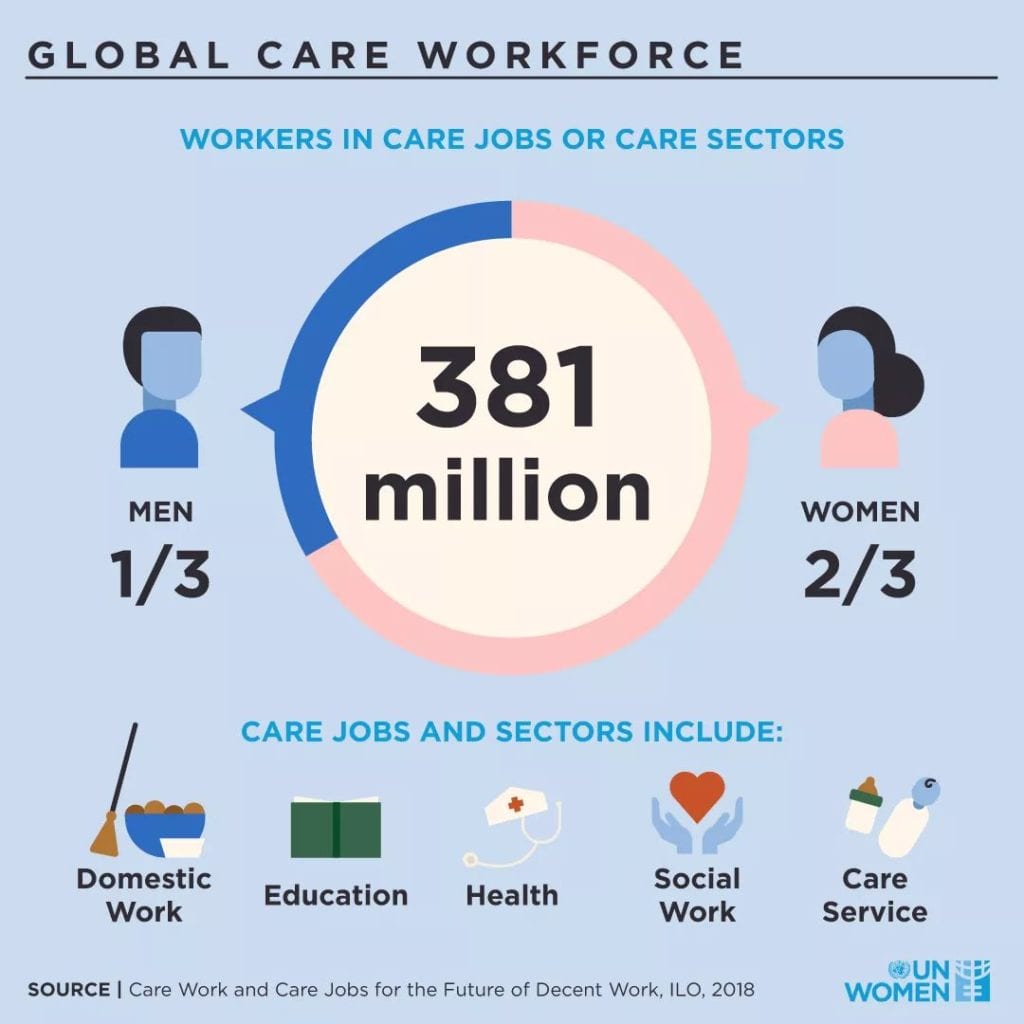

While COVID has created a global crisis of care for all countries, it has been women that have had to shoulder the burden of providing caregiving, particularly as the pandemic continues to expose the gaps and inadequacies of state-run care infrastructure and services in addressing this epidemiological emergency. Not only do women make up the majority of frontline workers, it has been women that have had to lose their career, jobs, and opportunities, to take on more care work. Women are the primary caregivers for children and the elderly around the world, a responsibility which has only intensified with COVID and the shutdown of childcare and education services, which saw 90% of children out of school. Research from UN Women shows that “women now spend nearly as much time doing unpaid care work as a full-time paid job. Women have also been forced to leave the workforce at alarming rates, rolling back progress towards gender equality.” Women’s unpaid labor and caregiving responsibilities are a key driver to their disempowerment compared to men, an inequality that has been further deepened by the pandemic, which has led to a recession of their hard-won economic rights and positions. While COVID has created a global crisis of care for all countries, it has been women that have had to shoulder the burden of providing caregiving, particularly as the pandemic continues to expose the gaps and inadequacies of state-run care infrastructure and services in addressing this epidemiological emergency. Not only do women make up the majority of frontline workers, it has been women that have had to lose their career, jobs, and opportunities, to take on more care work. Women are the primary caregivers for children and the elderly around the world, a responsibility which has only intensified with COVID and the shutdown of childcare and education services, which saw 90% of children out of school. Research from UN Women shows that “women now spend nearly as much time doing unpaid care work as a full-time paid job. Women have also been forced to leave the workforce at alarming rates, rolling back progress towards gender equality.” Women’s unpaid labor and caregiving responsibilities are a key driver to their disempowerment compared to men, an inequality that has been further deepened by the pandemic, which has led to a recession of their hard-won economic rights and positions.Many governments, corporations and societal organizations have taken for granted women’s roles in delivering care and invisible labor, profiting at the expense of their physical, economical, emotional and psychological well-being. The pandemic has laid bare the problem with a capitalist system that has been built on the patriarchal assumption that women will undertake the bulk of care responsibilities. 9-5 work weeks, limited or no paid family leave, lack of childcare facilities for working mothers and patriarchal corporate cultures, coupled with the addition of care responsibilities due to COVID overwhelmingly penalize women.

As stated by Relief Web International, “Women’s ability to earn a living or live a life free from poverty was already constrained by the heavy and unequal nature of unpaid care and domestic work. Globally, even before the pandemic hit, 42% of women of working age said they were unable to do paid work because of their unpaid care and domestic work responsibilities – compared to just 6% of men”. Studies also show that while unpaid and domestic care work has increased for both men and women as a result of COVID, women’s health, economic security and wellbeing are disproportionately affected. The COVID pandemic has caused a parallel pandemic of women with increased anxiety, depression, burn out, isolation and physical illness due to their increased unpaid care and domestic workload, contributing towards what has recently been termed as “the female recession”. According to Oxfam, “the pandemic cost women globally at least $800 billion in lost income in 2020, equivalent to more than the combined GDP of 98 countries.” As stated by Relief Web International, “Women’s ability to earn a living or live a life free from poverty was already constrained by the heavy and unequal nature of unpaid care and domestic work. Globally, even before the pandemic hit, 42% of women of working age said they were unable to do paid work because of their unpaid care and domestic work responsibilities – compared to just 6% of men”. Studies also show that while unpaid and domestic care work has increased for both men and women as a result of COVID, women’s health, economic security and wellbeing are disproportionately affected. The COVID pandemic has caused a parallel pandemic of women with increased anxiety, depression, burn out, isolation and physical illness due to their increased unpaid care and domestic workload, contributing towards what has recently been termed as “the female recession”. According to Oxfam, “the pandemic cost women globally at least $800 billion in lost income in 2020, equivalent to more than the combined GDP of 98 countries.”

At the Generation Equality Forum (GEF), COVID economies and its impact on gender equality, were at the forefront of the conversation, with participants from governments, international organizations, corporations, non-profits and civil society emphasizing the need to make pandemic responses both care- conscious and gender-responsive. GEF government commitment-makers, such as Canada, pledged $100 million to support paid and unpaid care work around the world, while other governments advocated for gender mainstreaming in national care infrastructure. Corporate commitment-makers promised to support feminist recovery through actionable policies such as creating caregiving leave for men, and encouraging them to take it. Civil society organizations, such as Promundo, highlighted the need to shift the narrative around men, boys, domestic work and caregiving as well as to enforce practices of redistributing unpaid care work.

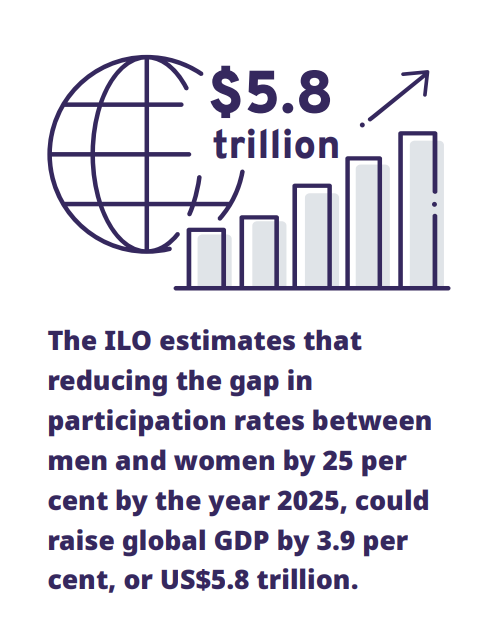

As stated by Project Syndicate, “Investment in care has been shown to act as a better post-pandemic economic stimulus than investment in traditional economic recovery approaches. Producing significantly less emissions than many other sectors, care jobs are also green jobs. Investment in care is a win-win as it can help to build a society that is more sustainable as well as more equal.”

While the GEF initiated important commitments that can start paving the way for feminist recovery, GEF coalition partners must work together to transform the global economy to center care and its related policies and infrastructure to allow for gender equality in both paid and unpaid labor. Commitment-makers must work to shift capitalist priorities from wealth to health, allocating large budgets to healthcare and social care to reflect the current needs of their populations. The GEF has made it clear that addressing the care economy is critical to women’s empowerment, and that that women must stop paying the cost of care, and redistribute it for a more equitable and sustainable society.

Ainab Rahman is a gender and security practitioner, and a member of the WFPG. She currently serves as Director at a global strategic advisory and intelligence company.

Return to top

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to devastate communities around the world, the value of factual information has become abundantly clear. Disinformation campaigns, racist propaganda, and a general lack of knowledge have cost the lives of thousands of people. Regrettably, this phenomenon is seen not only in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, but the HIV/AIDS epidemic as well.

Many of those who are infected with HIV have little to no access to trusted information or programming that can help curb the infection rate. As a result, at-risk communities must deal with a variety of preventable consequences. Furthermore, harmful stigmas about HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases can take root, which can be particularly dangerous for young women and girls who have been infected. In some instances, young women who have been infected with HIV will refrain from taking their medication when their parents are around because they fear being ostracized from their community if discovered, allowing the virus to rapidly multiply. UNAIDS estimates that in 35% of countries with available data, more than 50% of people report discriminatory attitudes towards people living with HIV.

In 2020, approximately 37.6 million people were living with HIV, with 1.7 million of those infected being under 15 years old. Although there has been a 30% decline in new HIV infections since 2010, many countries, including the US, have put HIV and AIDS prevention and response strategies on the back burner during the fight against COVID-19. Between 2019 and 2020, there were 700,000 fewer HIV screenings and 5,000 fewer diagnoses in the United States. On a global scale, roughly 680,000 people have died from AIDS-related illnesses since the start of the pandemic. This cannot become the norm. The World Health Organization estimates that unless HIV prevention and response strategies are accelerated, there may be half million excess HIV-related deaths in sub-Saharan Africa, increased HIV infections around the world, and a diminished public health response. With proper funding, HIV and COVID-19 infections can be mitigated, now and in the future.

Both vaccines or medication and trusted programming play important roles for those who are at risk of or already infected with a deadly virus. Studies have shown that education campaigns can delay initiation and frequency of sex, number of new partners, incidence of unprotected sex, and STIs and pregnancy rates. Furthermore, proper education and programming has proven to be one of the most cost-effective measures to take against disease spread. In 2010, Farnham et al. estimated that US HIV/AIDS prevention programs conducted from 1991 to 2006 saved $129.9 billion in medical expenses, and prevented 361,878 new HIV infections.

“Education as a vaccine” does not only apply to the fight against viruses and infection; it also plays a critical role in reducing gender inequalities and empowering women and girls. In the Generation Equality Forum session, “Young people, gender equality, and HIV: ending inequalities, ending AIDS”, Faith Onuh Ebere, an activist in Nigeria, explained how gender inequality is one of the top drivers of the HIV epidemic among adults, young women, and girls. She described how restrictive laws prevent young women from accessing contraceptives, increasing the risk of HIV spread due to unprotected sex. Women and girls accounted for 50% of all new HIV infections in 2020, and make up nearly 53% of all people living with HIV and AIDS. This means that the provision of proper programming and education to vulnerable communities not only reduces the spread of deadly viruses, but also empowers women and girls to exercise their bodily autonomy and fully embrace the extent of their human rights without the fear of repercussions, bringing benefits to us all. A few of these benefits include a safer, more robust society and a lower spread of HIV among all communities. In order to make this a reality, we must all advocate for education and programming—it could save your life someday.

Annika Bateman is a senior International Affairs and French Studies double major at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, OR. She interned at the WFPG during Summer 2021.

Header photo: Mother and child at an HIV/AIDS clinic in Maputo, Mozambique. By Talea Miller, PBS NewsHour.

Return to top

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has created many new challenges for the world, the discrimination facing Indigenous women in Latin America has always existed. However, their societal exclusion has reached unprecedented levels since 2019. According to the UNFPA, Indigenous peoples face a higher risk of infection due to a lack of access to safe water for handwashing, a main measure to prevent further spread of the virus. Furthermore, the current economic situation facing Indigenous women is precarious: UN Women estimates that 6 million rural and Indigenous women in the Latin American region are at risk of falling into extreme poverty due to the effects of COVID-19.

Native women and girls are currently in a vulnerable situation, intensified by the effects of the pandemic - but it isn’t irreversible. One way to empower these communities is to include their traditional knowledge into COVID-19 response strategies. By giving Indigenous women their long-deserved seat at the table, they can both empower themselves and help their countries successfully emerge from the pandemic.

Across generations, Indigenous communities have created coping mechanisms grounded in traditional knowledge to different circumstances affecting their communities. For COVID-19 specifically, traditional teachings have proven to reduce symptoms of the virus, and practices, such as ubaya/tengaw, a state of rest after hard labor or disasters practiced in the Cordillera in the Philippines, have prepared Indigenous communities for quarantine procedures. During lockdowns, communal practices come into effect, such as the binnadang/ub-ubbo, where community members extend help to those in need.

However, even in quarantine, Indigenous populations around the world still face violence and insecurity, which, in some cases, has intensified due to compliance with government-mandated pandemic responses. For some, restrictions on movement have infringed on Indigenous people’s right to adequate food by barring them from accessing land, natural wealth, and resources. For instance, the San people in Botswana were unable to access government permits that exempted people from movement restrictions to allow essential activities, such as resource collection. In Asia, where Indigenous women have always faced harassment, rape, imprisonment and murder, COVID-19 has only worsened the violence. To be sure, Indigenous men are not completely immune to the shadow pandemic. On March 23, 2020, Indigenous leaders Omar and Ernesto Guasiruma of the Embera people of Colombia were murdered in their homes while complying with lockdown procedures.

COVID-19 is not only exposing the violence and discrimination that Indigenous women and girls face every day; it has further revealed the impact of climate change on native communities. Some groups, such as the Orang Asli, the aboriginal people of Peninsular Malaysia, have returned to the forest as their defense against the pandemic and source of sustenance. However, deforestation, the extractive industry, and the introduction of genetically modified species have prevented Indigenous communities from accessing the land, leaving them vulnerable to food shortages during the pandemic. Between 2016 and 2018, deforestation rates rose 150% in Indigenous territories in Brazil, destroying key resources and obliterating a crucial part of the Amazon’s carbon sink.

In order for countries to successfully emerge from the pandemic and build a “better normal”, Indigenous knowledge must be incorporated into COVID-19 response strategies. For environmental policies, traditional resource use and management practices can lessen the risk of food shortages and mitigate the effects of climate change. Although Indigenous communities comprise less than 5 percent of the world’s population, they protect 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity. This means if national governments were to use Indigenous knowledge in this area of policy-making, we would all prosper. Environmental degradation would be greatly curbed if the sovereignty of Indigenous lands was better protected, lessening the risk of a future global pandemic as the human relationship with nature is rebalanced.

The use of traditional Indigenous lockdown procedures would be particularly advantageous for governments as well. The principles of ubaya/tengaw and binnadang/ub-ubbo are illustrative examples of the established rituals Indigenous communities have when faced with crises. Although countries have created their own lockdown protocols during the pandemic, the use of Indigenous language when formulating regional policies would be more culturally appropriate and foster greater communication between governments and native peoples. Furthermore, advocacy for the concept of ayyew, a term also from the Cordillera in the Philippines meaning to not waste anything, would mitigate the use of excess resources throughout times of national struggle. This policy could be particularly crucial in the event of food shortages during and after the pandemic.

In Bolivia, Las Cholitas Escaladoras, are a group of Indigenous women who climb mountains in Latin America to spread awareness for the prevention and elimination of all forms of violence against women. Last year, their goal was to reach the summit of Huayna Potosi, at 6,000 meters above sea level. Image Source

|

This summer, the Generation Equality Forum hosted multiple sessions on the current issues facing Indigenous communities. I attended an event on “The inclusion of indigenous women in responses to the crisis and recovery from COVID-19”, which began with a video of Las Cholitas Escaladoras, a group of Indigenous women activists in Bolivia who climb mountains in traditional dress, shattering stereotypes and raising awareness for the violence committed against Bolivian women. In the session, Indigenous women from all over the world shared their experiences and advocated for the inclusion of native women in COVID-19 recovery responses to empower both Indigenous communities and countries as a whole.

By implementing native knowledge into policy responses, Indigenous rights can be respected, Indigenous women can be empowered, and Indigenous voices can be heard at future policy discussions. Although the COVID-19 pandemic is a new 21st century challenge, traditional knowledge may be the key to building a safer future for all.

Annika Bateman is a senior International Affairs and French Studies double major at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, OR. She interned at the WFPG during Summer 2021.

Header photo: Indigenous women in Guatemala have less access to services, such as education, limiting their possibilities for employment and income. Investing in native communities and boosting Indigenous women’s entrepreneurial abilities can grant them economic autonomy and help them escape from violence. Photo Credit: CarlosVanVegas

Return to top

In 2019, one of the editors of the recently published open-access book Women and the UN: A New History of Women’s International Human Rights asked me to contribute a chapter on the history of UNSCR 1325, with a focus on the women who were instrumental in its birth. Her request brought me up short. While I had written much about the implementation of UNSCR 1325, I was unfamiliar with its creation beyond the role played by civil society. I needed to learn more to write my chapter that examines how, in a UN Security Council composed of almost all men, the Security Council unanimously adopted the first resolution on Women and Peace and Security, UNSCR 1325.

At the start of my research, I began with a deficit. I knew none of the actors. After reviewing the existing material and literature on the creation of UNSCR 1325, as well as examining relevant Security Council transcripts, I compiled a long list of people I wanted to interview and reached out to individuals and organizations--including the WFPG--who might be able to help connect me to the persons I wished to interview.

As a result, I had the good fortune of being able to interview every single living woman who spoke at the UN Security Council Open Debate on UNSCR 1325: UNIFEM Executive Director Noeleen Heyzer; Ambassador Claudia Fritsche of Liechtenstein; Parliamentarian Krishna Bose of India; Jelena Grčić Polić of Croatia; Ambassador Penny Wensley of Australia; and Ambassador Nancy Soderberg of the US. I also was able to interview many who spoke at the Arria Formula meeting, to include Luz Méndez Gutiérrez, the peace negotiator who successfully fought to include rights for women in the Guatemalan peace accords. I am shocked that her recent death was and is not widely reported.

Noeleen Heyzer, in order to include me in her schedule, skyped with me at almost midnight her time in Bangkok. Heyzer, during the course of the interview, disclosed never-before revealed particulars of the internal pushback made against her as she worked on the Arria Formula meeting that helped convince members of the UN Security Council that UNSCR 1325 needed to be adopted. Her newest book, Beyond Storms and Stars - A Memoir, will be available in the US in September 2021. It addresses her journey to the position of Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations while exploring the difference that UNSCR 1325 made for women caught in conflict and on the UN system itself.

Parliamentarian Krishna Bose, the only woman as of 2020 to have chaired the Indian Parliamentary Standing committee of External/Foreign Affairs, died three weeks after responding in writing to my questions. That shook me. That day I could not stop crying. I had asked her hard questions, to include the difference between two Indian Parliamentarians at Beijing+5: Bose and Phoolan Devi. Assassinated in 2001, Phoolan Devi had served in prison (without trial) for extrajudicial actions of damaging or dismembering penises of unprosecuted rapists. Parliamentarian Krishna Bose informed me that Devi “brought out [to Beijing+5] the stark reality of the situation while we were discussing women’s issues only theoretically.” Sugata Bose, a Harvard professor, a member of India’s Parliament and a son of Krishna Bose, tells me the inaugural Krishna Bose Lecture occurred in Calcutta on December 26, 2020.

During the course of my research, it became clear to me how imperative it is to record our history before it is lost. My hope is that this chapter on UNSCR 1325 will spur other participants to write their histories. Recently I received an email from one of my interviewees, civil society activist and Arria Formula speaker Inonge Mbikusita-Lewanika, sharing that she is planning to publish her papers and statements on Women and Peace. I hope that others will follow her example.

Writing this history of the creation of UNSCR 1325 awoke in me appreciation of, and gratitude toward, those who had the vision and grit to create UNSCR 1325. It made me realize that we need to ensure we do not subscribe to the prevailing mode of history, that of erasing all but a few of our heroines, but instead to realize, like the creation of UNSCR 1325, our history is the result of many. It also awoke in me the desire to continue my explorations post-COVID, to include exploring (1) the archives of those who died before I could interview them, including Assistant Secretary-General Angela King, (2) the gender histories of the Member States that sponsored and supported UNSCR 1325, including the pro and anti suffrage forces in Liechtenstein, and (3) to learn more about the internal story of the Member State that sponsored UNSCR 1325, Namibia.1

Cornelia Weiss is a former colonel, having served in the Americas, Europe and the Pacific. Honors received include the US Air Force Keenan Award for making the most notable contribution to the development of international law. Knowing that history is often used as an excuse to exclude women, she excavates forgotten history about women, peace, and power.

Header photo: from left, Luz Mendez (Guatemala), Faiza Jama Mohamed (Somalia), Noeleen Heyzer (Singapore), Angela King (Jamaica), and Inonge Mbikusita-Lewanika (Zambia), 2000. UN Photo

1Through engaging with Namibian “penholder” Aina Iiyambo, I was able to begin exploring "insider" insights into the drafting of UNSCR 1325; however, I was not able to obtain any of the working drafts of what became UNSCR 1325. I hope post-COVID that these will emerge with help from readers of this blog.

Return to top

On September 2, the Women’s Foreign Policy Group hosted a panel with Rina Amiri, Gayle Tzemach Lemmon, Ambassador Melanne Verveer, and Dr. Alyssa Ayres for a discussion on Afghan Women in Crisis. For those of you who missed the conversation, we highlighted some of the main discussion points.

“[Afghan women are] victims but also agents…They have to be seen as strategic allies and assets rather than as victims and collateral damage of a war gone too long.”

- Rina Amiri

Sobering pictures and stories coming from Afghanistan have flooded our media over the past few weeks. We have read about the fear that has gripped families as normality quickly evaporated. We have heard about the loss of hope as young people watched the future they built collapse before their eyes. We have seen searing images of Afghans desperately clutching the fuselage of US military planes flying out of Afghanistan for the last time. Afghans are in crisis. Afghan women are in crisis.

We must, however, not fall into the trap of otherization, marking these stories as something that happens on the other side of the world. These young people, women, and families are just like us, our families, and our friends. They share similar dreams. And until recently, they shared similar fears. In responding to the Afghanistan crisis, we cannot let physical distance desensitize us.

Since the 1990s, Afghanistan has become more educated and urban by every indication. In 2018, girls made up 38% of students, with rapidly growing rates in higher education as well. The Afghan women’s robotics team made international headlines in 2017, illustrating how much opportunities for women had expanded over the past two decades. And while more needed to be done, the advancements in recent years and the hard work of Afghan activists created an environment where the greatest concern for many young women was their university studies—a great contrast to the years of Taliban rule in the 1990s. Within a matter of weeks, Afghan girls went from having to worry about their upcoming homework assignment to forced marriage at the hands of the Taliban.

The impact of Afghanistan’s fall on Afghan women is further illustrated in healthcare. For years, Afghanistan has been one of the worst countries for maternal and child health. In 2000, 1,450 women died for every 100,000 live births; in 2017, while still very high, the number had fallen to 638. For comparison, the women’s mortality rate in OECD countries is 17 deaths per 100,000 live births. This is just one of many health impacts; the improvements from the past two decades are now in jeopardy. In the face of the drastically altered security, education, and healthcare landscape, many find themselves asking, now what? What can we do to help the humanitarian catastrophe, protect the lives of Afghan women, and contribute to stability within Afghanistan?

First, before the United States can do anything, it needs to reassess its mindset in approaching the situation. US policymakers need to stop thinking they can dispose of Afghanistan and redirect their focus and resources to East Asia. We live in an increasingly interconnected world, and the problems in Afghanistan are not going away. This, along with the humanitarian crisis, necessitates continued resources directed toward Afghanistan’s most vulnerable populations.

Second, building on this mindset shift, US policymakers must remember their legal obligations under the 2017 Women, Peace, and Security Act. With this act, the United States committed itself to “women’s meaningful inclusion and participation in peace and security processes to prevent, mitigate, or resolve violent conflict.” The United States has obligations to support Afghan women in the peace and security negotiations that it needs to fulfill.

Third, there are immediate actions the United States should take to support high-risk Afghan women, such as expanding its humanitarian parole program. Humanitarian parole “is used to bring someone who is otherwise inadmissible into the United States for a temporary period of time due to an emergency.” While the State Department recently announced a small program to fund this effort, more funding is needed, as this can be one of the fastest ways to help at-risk Afghan women and activists.

Fourth, while US leverage is significantly weaker now than it was before withdrawal negotiations began, US policymakers need to use their remaining leverage points to influence the outcome and stability of Afghanistan. But before diving into these remaining leverage points, it is important to note how a shift in US language and narratives resulted in a loss of negotiating power.

Before the withdrawal negotiations, US policymakers stood firm to their promise that women’s rights would be a priority. However, once these negotiations began, this narrative shifted and became ‘women’s rights are an internal affair for the Afghan people to solve.’ The new narrative created an environment that emboldened the Taliban to disregard women’s rights and women’s role in society. The narrative shift also left women out of the withdrawal negotiations, drastically reducing the possibility of a durable peace and inclusive framework.

But even with this significant loss of credibility and leverage, the United States, along with the international community, still has leverage points it can use to influence the security situation in Afghanistan. The Taliban desperately want international recognition, a diplomatic platform, and financial assistance. Providing this desired recognition and diplomatic platform, unfreezing assets, restarting aid, and wielding targeted sanctions remain powerful tools in the US and international arsenal. It is also important to remember that the Taliban are not a monolith.

Finding negotiating partners more willing to make concessions will be critical in the effort to establish stability and moderate the regime’s rule.

Fifth, the United States needs to work with international institutions to turn the fragmented regional response into a coherent voice with greater leveraging power. No state benefits from Afghan instability; each Middle Eastern country would prefer a return to some sort of normalcy. For many, Afghanistan is a critical trade partner, as evidenced by Iran’s recent decision to restart fuel exports to Afghanistan. The region’s collective economic and diplomatic power gives it a unique opportunity to influence moderating and stability efforts in Afghanistan.

As we look for ways to restore stability and protect Afghan women in crisis, we must keep in mind Rina Amiri’s remarks. Afghan women are victims and agents. We need to provide humanitarian and financial assistance to help evacuate high-risk Afghan women and provide resources for those who wish to stay behind. But we also need to treat Afghan women as the agents of change they are. These women are resilient. These women have worked hard over the past years building the future they wanted to live. They need to be a part of these leveraging and security negotiations. It is not an option for Afghan women to be invisible.

Maggie Sparling is a junior at the University of Virginia majoring in History and Economics, and minoring in Foreign Affairs. She interned at the WFPG during Summer 2021.

Return to top

Since the launch of the first official feminist foreign policy by Sweden in 2014, centering the security of women and girls, promoting gender equality, and gender mainstreaming in foreign affairs have become increasingly common. Since 2014, Canada, France, Mexico, Luxembourg, and Spain have adopted feminist foreign policies. Libya followed suit this year, announcing its adoption of a feminist foreign policy at the Generation Equality Forum (GEF) in July.

Although there is no universal definition of a feminist foreign policy, the Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy defines it as a multidimensional, intersectional political framework centered around the wellbeing of women and marginalized people. It departs from the traditional focus on military force and violence, rethinking security from the viewpoint of the most vulnerable. Through elevating marginalized groups’ experiences and agency, feminist foreign policies seek to scrutinize destructive hierarchical forces such as patriarchy, colonization, capitalism, racism, and militarism. The International Center for Research on Women identifies five key components that make an impactful feminist foreign policy: purpose, definition, reach, intended outcomes and benchmarks over time, and plans to operationalize. A feminist foreign policy goes beyond adding “women’s issues” or “gender” to a foreign policy agenda. Rather, feminist foreign policies use gender as an analytical lens, ensuring that the unique needs of gender minorities are considered in policy making. For example, Canada includes feminist approaches to climate action and global economic growth as two of the six action areas of their Feminist International Assistance Policy, while Sweden is guided by the “three R’s”: resources, representation, and rights. No matter the framework, a feminist foreign policy is intersectional and grounded in the promotion and protection of human dignity, viewed as central to ensuring peace and security.

Mexican President, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, speaks at the opening ceremonies of the Generation Equality Forum in Mexico City (March 2021). Image Source

|

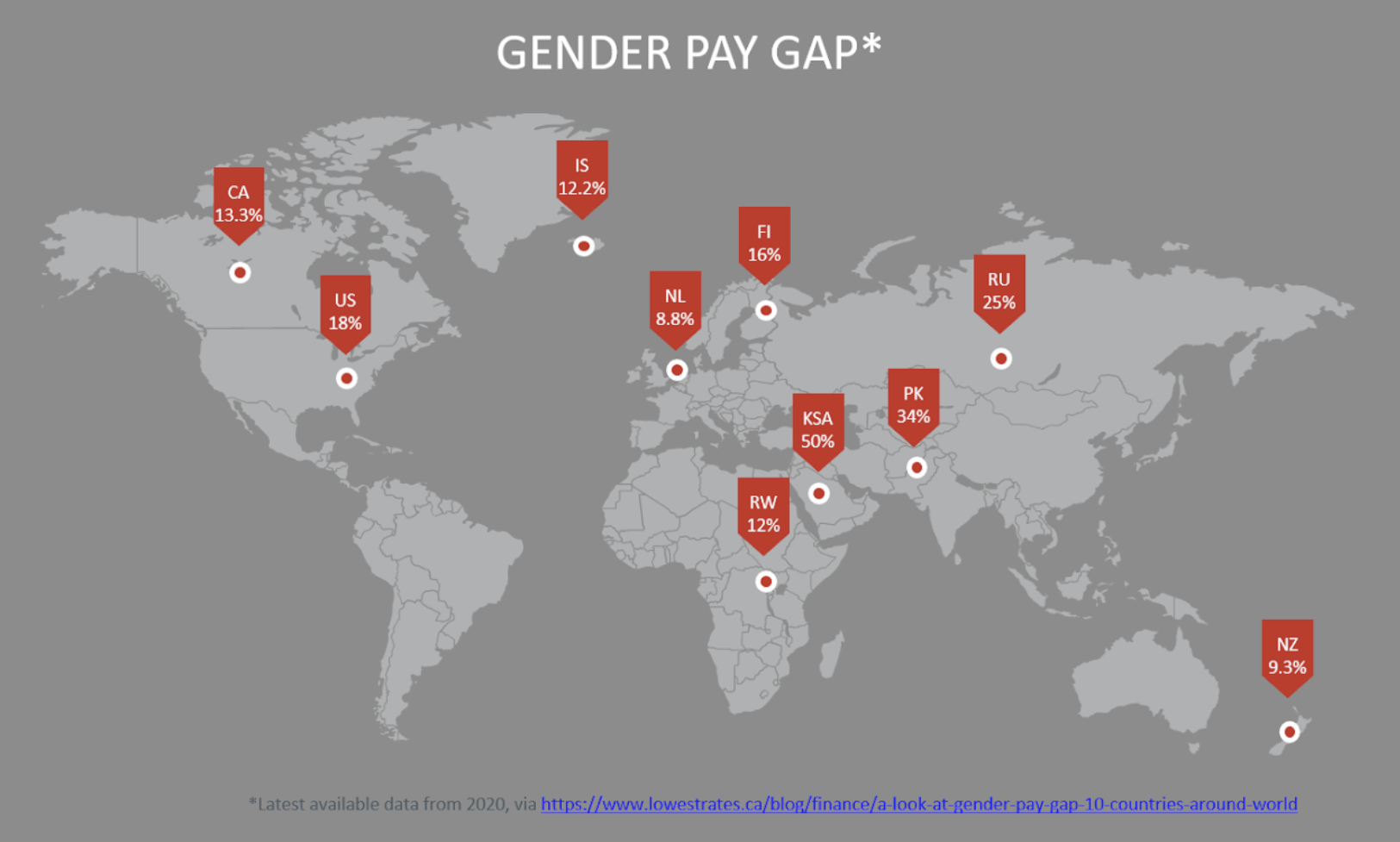

So far, feminist foreign policies have directly increased women’s representation in political office and peace efforts, created or strengthened legislation preventing sexual exploitation in multiple countries, bolstered female entrepreneurship, and more. For the countries that adopt a feminist foreign policy, the positive effects aren’t just limited to those abroad - they also include vital reforms at home, such as progressing gender equality and equity in the workplace. Sweden’s mandate to increase female representation in leadership has led to women holding over half of all management positions, including an increase in female Ambassadors from 28% in 2006 to 40% in 2016. Feminist foreign policy has also facilitated continuous reviews of wage developments to close the gender pay gap in the Foreign Ministry. Moreover, by using gender as a common lens of analysis, collaboration between portfolios and offices is more efficient and innovative. Implementing a feminist foreign policy has ushered a complete institutional and cultural shift which has empowered those working in Sweden’s foreign policy.

With its emphasis on intersectionality, dignity, and human security, feminist foreign policies could be exactly what the world needs to build back better from the COVID-19 pandemic, and the resulting backsliding in women’s rights. However, we must not be hasty in hailing feminist foreign policies a panacea to the world’s problems. Many countries that promote their adoption of “feminist” foreign policy still continue to perpetuate “status-quo” foreign policy activities. Was Canada’s foreign policy feminist when they sold Saudi Arabia C$1.311 billion in military exports last year? Feminist foreign policies are inherently anti-militarist, as women and girls are disproportionately impacted by armed conflict. This move also comes in direct contradiction to Canada's commitment to “reducing threats and to facilitating stability and development in fragile states and states affected by armed conflict,” part of its Feminist International Assistance Policy. It’s also difficult to legitimize feminist foreign policy in countries where high levels of gender-based violence, gender inequality, and misogyny persist domestically. Can we trust Mexico's commitment to implement reforms to eliminate gender-based violence in the Foreign Ministry, while it is facing a femicide epidemic and state forces are regularly implicated in committing violence against women?

It’s also important to note that foreign policies can be feminist without being outwardly labeled as such. In the Netherlands, gender mainstreaming in foreign policy has been a long standing practice. By gender mainstreaming, the Netherlands is able to implement gender analysis more seamlessly than other countries that limit “gender” to an office, portfolio or “add more women and stir” for a gender perspective. The operationalization of feminist principles within foreign policy is more important than subscribing to a feminist foreign policy in name only.

Despite the flaws and limitations it currently faces, feminist foreign policies are a necessary step towards achieving security, peace and equality globally. The GEF has shown us that there is a greater acceptance of the fact that the world is gendered; and to combat this, the state can no longer be gender-blind in its policymaking. However, feminist foreign policies cannot stand alone - they are one piece of a gender-equal governing regime. For states to truly commit to feminist governance, they must completely overhaul the their approach to policymaking. They must continually engage with those who will hold them accountable - activists and civil society - and disengage with forces of misogyny and violence. Feminist foreign policies will reach their full potential when all states lead with politics of compassion rather than self-interest, acting to ensure the dignity and equality of all people, without exception.

Indigo Stegner is a Senior at the George Washington University, majoring in International Affairs and minoring in Spanish and Cross-Cultural Communication (Anthropology). She was an intern with the WFPG from January-August 2021 and led their research and outreach efforts related to the Generation Equality Forum.

Header Photo: Federica Mogherini HRVP at the European Council, Brussels (October 2018). Image Source

Return to top

The 2021 Olympics has been a year of firsts for representation in sports. From gymnast Sunisa Lee, the first Hmong American to win a gold medal, to weightlifter Hidilyn Diaz, the first to win a gold medal for the Philippines, women are coming out on top of their game in the Olympics, which has seen the highest amount of gender representation in the history of the sporting event. The Olympics in Tokyo boasted 49% participation of women (equaling nearly 11,000 athletes), compared to 45% at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Games and 44.2% at the 2012 London Olympics. This year’s Games also saw the inclusion of its first ever openly non-binary athlete, Alana Smith, an American skateboarder, and the first ever transgender athlete, Laurel Hubbard, a weightlifter from New Zealand.1

But despite some of the strides that women, BIPOC and LGBTQ+ groups have made at the 2021 Olympics, this year has shown that there are still many challenges that lay ahead in reforming archaic and traditional rules and perceptions around gender, race and sports. While events like the Olympics can be a platform for change, they can also reinforce the gender and race-based discrimination historical in the sports industry. Whether by banning swim caps for Black swimmers with natural hair or reinforcing hypersexualized clothing in certain events, these types of policies force women to conform to a Eurocentric male gaze. Women athletes may protest (as did the German gymnastics team in the Olympics who refused to wear the mandated leotards), but their non-compliance can cost them (such as with the Norwegian women’s handball team in the Euro 2021 tournament when they refused to wear the regulation high-cut bikini bottoms). Such policies – often set by organizing bodies dominated by men2 – have consequences on the full and equal participation of women in sports.

American track and field athlete Gwen Berry received harsh criticism for turning away from the US flag and national anthem while on the podium for an awards ceremony in June. Berry has accused critics of her protest of favoring "patriotism over basic morality." Though the Olympics strives to be neutral, it has a history of protest at the podium, and recently changed its guidelines to allow peaceful expressions of protest in support of racial and social justice. This year’s Games also saw a number of athletes take the knee in support of social justice issues.

|

The sports industry has also fostered a culture of impunity when it comes to the treatment of women athletes, often turning a blind-eye to their emotional, physical and sexual exploitation and abuse. USA Gymnastics’ routine dismissal of sexual abuse allegations against coaches is a prime example of this, as is the harsh criticism faced by Gwen Berry, Naomi Osaka and Simone Biles for standing up for their own needs and experiences. The sports industry has historically shown that it does not have an interest in protecting its women athletes. Despite having the responsibility to win gold for their countries, women athletes are constantly devalued, given less pay, less resources and less airtime.

This year’s Generation Equality Forum (GEF) in Paris set out to address some of these issues, highlighting the importance of women in sports as an important driver for gender equality around the world, and asking for commitments to support women’s leadership, participation and coverage. UN Women Executive Director Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka reaffirmed the necessity of public and private sector actors to make investments in women in sports, whether it be through allocating resources and funds for women, or changing laws and policies to increase access and opportunities for women in safe and inclusive environments in the industry. The three-day gender summit also saw the announcement of the launch of the Global Observatory for Women and Sport, a Switzerland-based institution for research and data.

As society changes to integrate measures for meaningful equality and inclusivity, so should the sports industry, its organizers, its events and its policies. The GEF’s participants have made commitments to support those initiatives, so that while women athletes continue breaking records and winning gold, they don’t have to go the distance alone.

Ainab Rahman is a gender and security practitioner, and a member of the WFPG. She currently serves as Director at a global strategic advisory and intelligence company.

Header Photo: Hidilyn Diaz, the first to win a gold medal for the Philippines in their nearly 100 years of participation in the 2021 Olympic Games. She set an Olympic record, lifting a combined weight of 493 pounds, across two lifts.

1While the Olympics have allowed a white transgender athlete to participate in a woman’s event, Namibian cis-women athletes Christine Mboma and Beatrice Masilingi were disqualified from the 400-meter race at the Olympics because of their naturally high levels of testosterone. In order to compete, they would have to take medication to lower their testosterone levels. This builds on the 2019 decision to exclude South Africa’s Caster Semenya, who was ruled to be intersex and was asked to take testosterone suppressants to continue to compete.

2In the International Olympic Committee, women make up 33.3% of the executive board, and 37.5% of committee members are female.

Return to top

Artificial intelligence (AI) and other emerging technologies have long been heralded for their potential to dramatically change the way we live, conduct business, and view security. From healthcare to transportation logistics to military weapons, these technologies will alter our everyday lives. The manner and direction of that change, however, depends on how it is governed.

Regulatory frameworks and international technical standards, largely undeveloped for AI and emerging technologies, play an instrumental role in governing the deployment of these systems and the norms and values surrounding their use. For the first time, Western democracies will not write the rules by default. China is playing a growing role in international technical standard bodies, leading at least four such organizations. Declining Western influence coupled with Beijing’s rise changes the playing field. Whoever controls the development of AI and emerging technology frameworks controls access and use of these technologies. The stakes are high.

Theoretically, democratically-minded countries develop these frameworks in a way that protects and perpetuates democratic norms and values. They adopt a human-centered approach and focus on values such as transparency, privacy, and shared prosperity. Advocates of this view can point to the peaceful and civilian use of GPS systems worldwide and widespread inclusive access to the internet as examples of this model’s success.

If, however, countries with a repulsion for democratic values and human rights are left to write these frameworks, we cannot expect transparency, privacy, and shared prosperity to be guiding principles. Instead, we can expect these technologies to be normalized for surveillance, censorship, misinformation, and disinformation. One need only look to China’s extensive use of AI systems in Xinjiang and the growing prevalence of cybercrimes and AI facilitated terrorism to highlight this possibility.

With the recent Pegasus spyware revelations, it may seem that democratic countries are contributing to this dangerous normalization. But even though Western clients may use these technologies for targeted surveillance purposes, there is still a stark divide in the way democracies and authoritarian countries like China would write the rules of the game. The Chinese model poses a greater threat to human rights and individual freedoms, and through its actions, it is normalizing surveillance and disinformation on a much greater scale. Leaving the design of international regulatory and standards frameworks to authoritarian-guided countries would be anathematic to goals of an inclusive, civilian, and human-centered approach.

Democratically-minded countries are better suited for this effort. But this does not mean that we can blindly place control in their hands. Governmental bodies are not predestined for an altruistic and inclusive outcome, as evidenced by their long and troubled histories of using the system to oppress marginalized communities. Safiya Umoja Noble’s research highlights numerous such examples as she analyzes how search engines and algorithms reinforce bias and systemic oppression. Her work is only the tip of the iceberg. This leads us to realize that while democratically-minded countries are the best suited governmental bodies to lead this international effort, they cannot do it alone.

Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin speaks at the 2021 Generation Equality Forum. Finland is leading GEF's Tech and Innovation for Gender Equality Action Coalition.

|

Government leaders must work with a diverse coalition of stakeholders to write and implement an inclusive regulatory and standards framework. This coalition must include civil society, academia, and the tech industry in order to be truly transformational. The recent Generation Equality Forum (GEF) offers a good starting place for developing this initiative, as GEF consciously built alliances across these sectors. One of its civil society action coalition partners, <A+> Alliance, recently launched the Feminist AI Research Network. The network is dedicated to making these technologies inclusive, by working with the industry to rethink how it prototypes and designs the technology. Additionally, the network has the necessary infrastructure to guide an inclusive approach to the research and pilot programming, which drives these regulatory efforts. This is only one of many civil society partners who can play an instrumental role in maintaining accountability and helping governments achieve these goals.

The tech industry, too, has a critical role to play in this coalition—especially given how the private sector drives the lightning pace changes in the field. Microsoft and Salesforce partnered with GEF’s Technology and Innovation Action Coalition and committed to furthering gender equality in the technology sector. Bringing private industry committed to inclusive technology use into the coalition and subsequent negotiations is necessary to normalize democratic values in technology deployment and the regulatory framework.

We need to raise awareness of the impact international technical standards and regulations have on the norms associated with their use. GEF offered a great start with events such as ‘Charting the Path for Feminist and Inclusive Artificial Intelligence’ and ‘Towards an International ISO Standard for Gender Equality.’ But we need to broaden this effort. Raising awareness helps to bring traditionally marginalized groups to the design centers, research labs, and regulatory negotiating tables. To build a truly inclusive set of norms surrounding emerging technology deployment, that inclusivity needs to be mirrored in all steps of the process.

Combining democratically-minded countries’ values and the power, passion, and accountability that comes from a diverse coalition of stakeholders, we can design a regulatory and standards framework that is inclusive, promotes shared prosperity, and is human-centered in design.

Maggie Sparling is a junior at the University of Virginia majoring in History and Economics, and minoring in Foreign Affairs. She is interning at the WFPG for Summer 2021.

Return to top

We have all watched as the curtains close on yet another UN event, criticized as just another opportunity for governments to make empty promises, their platitudes never transforming into practical policy. Days, months, and often years of stagnation leave us questioning whether these international events can inspire real and actionable change. Yet the UN Women’s Generation Equality Forum (GEF) was designed to be different. In order to counter the type of inaction we witnessed following the 1995 World Conference on Women in Beijing, the GEF was specifically built around a framework of accountability. But for this to have any hope of surviving past GEF’s initial momentum, and to ensure that it does not just become an empty promise, there is one foundational measure that must be addressed: data.

While not the most glamorous solution, data is vital. It is key to enforcing effective policies and maintaining transparent accountability, working to meet the needs of targeted populations and the goals of development on local, national, and international levels.

We have, however, only 22% of the data needed to monitor progress on gender-specific Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) indicators. Of this data, a frightening 23% is from 2010 or later and only 16% is available for more than two points in time. More than one hundred low- and middle-income countries lack adequate civil registration, statistics systems, and trained professionals to collect the necessary data in the first place. Poor collection and analysis infrastructure and data gaps disproportionately affect women in marginalized groups, rendering them practically invisible in official statistics. These types of data gaps, if left unfilled, will have far-reaching consequences, not only on SDG progress, but also on equity and development on a global scale.

But simply collecting more data is not sufficient. There are many well-documented cases of biased data and its detrimental impact on policy rollout and outcomes for women and marginalized groups. While expanding the general data pool can be helpful, what we need is a global gender-disaggregated data effort.

Gender-disaggregated data, or ‘gender data’ is information broken down by sex or data that primarily impacts women and girls. It is necessary to quantify and explain women and girls’ participation in society and measure changes in their outcomes over time. While 80% of countries produce sex-disaggregated data for mortality, labor force participation rates, and education/training—and the reliability of these data collection efforts and their ability (or willingness) to document marginalized communities vary greatly—less than 33% collect gender-disaggregated data on informal employment, entrepreneurship, unpaid work, and violence against women—all categories that disproportionately affect women and girls.

We desperately need a concerted effort to collect gender data, and this endeavor must be launched soon to capitalize on GEF’s momentum. GEF action coalitions must meet to organize and support gender data efforts, to develop the infrastructure and capacity necessary to collect and analyze this information, and to create a framework which can use its insights to foster better policies and practices. With precise gender data, GEF action coalitions can design the M&E frameworks needed to hold governments, organizations, and institutions accountable to their commitments, and to monitor their progress in creating gender-inclusive policy shifts.

Additionally, UN Women should work with its action coalition partners and other international organizations to develop a centralized data center and encourage its partners to use the data in developing and monitoring policies and initiatives. UN Women, the OECD, and the World Bank have already started public databases dedicated to making gender-disaggregated data open and accessible. As data collection efforts expand, it is imperative that new data is uploaded to these centralized databases. Open data is vital for transparency, public service improvement, social innovation, economic growth, and boosting efficiency. Open data in general can help us unlock $3 trillion in annual economic potential within the global economy.

We have the momentum, and we have the attention of global leaders across governments, philanthropic organizations, the private sector, and civil society organizations. GEF action coalition leaders must meet this year to develop these data collection efforts, design the monitoring and evaluation frameworks, and schedule follow-up meetings to track the progress and make changes as needed. A desire for accountability and a focus on data has given us a unique opportunity to recast the scope of what is possible through UN conventions and forums. Let’s take advantage of this moment.

Maggie Sparling is a junior at the University of Virginia majoring in History and Economics, and minoring in Foreign Affairs. She is interning at the WFPG for Summer 2021.

Return to top

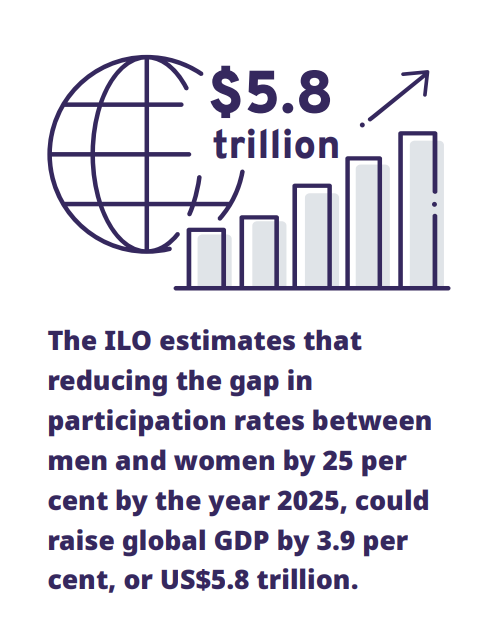

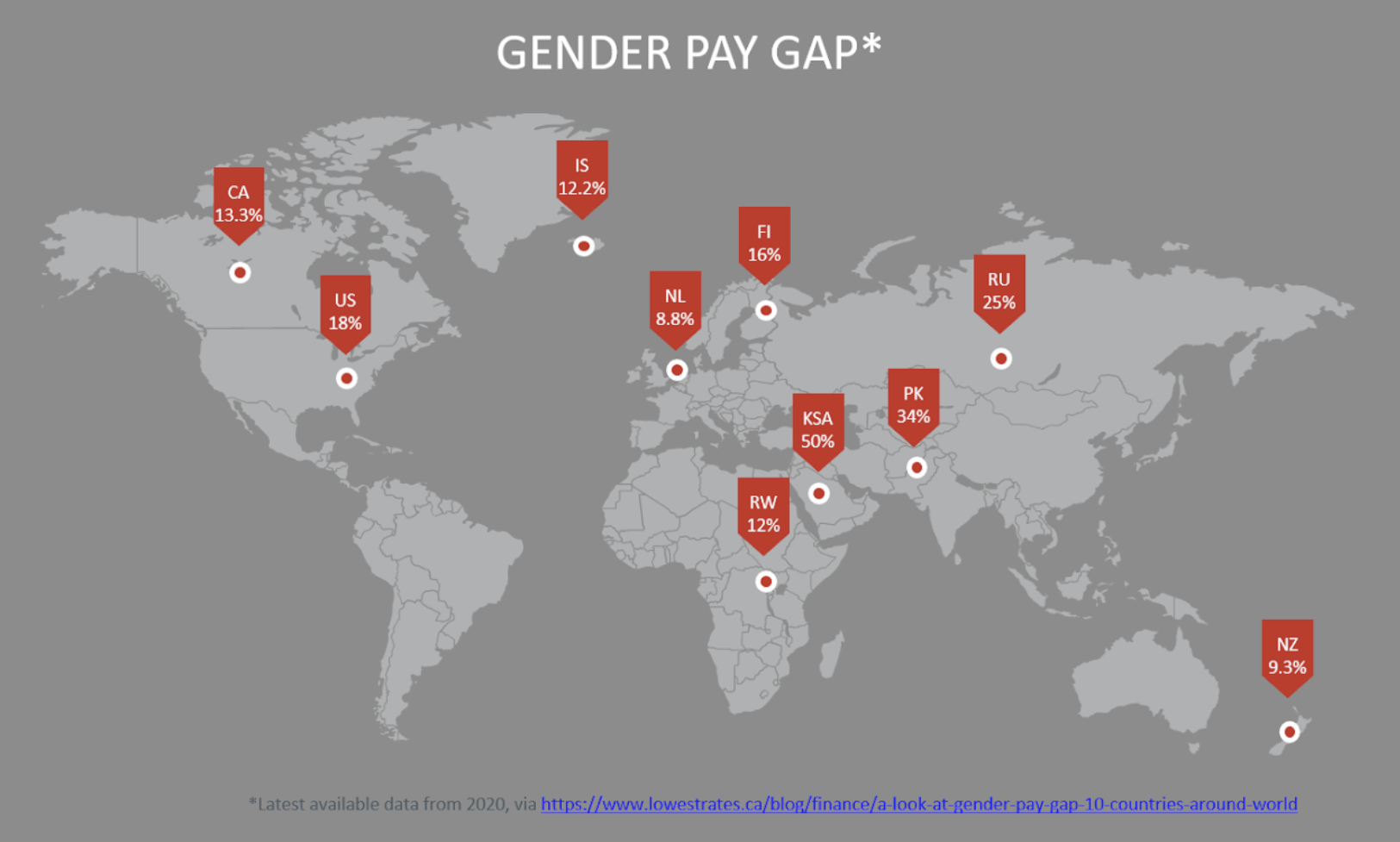

While the Generation Equality Forum (GEF) highlighted numerous government agencies and civil society organizations that are working towards progressing the gender agenda, the Forum emphasized how real success, especially in the area of economic justice and rights, requires partnerships across the public and private sector to comprehensively meet the equality-based targets set forth during the three-day summit.

The GEF showcased a number of private sector actors that are making commitments to build multi-stakeholder consensus and adopt new ways of thinking and working that are more aligned with equality. From reaching gender pay equity by 2025 and ensuring living wages for all, to enforcing gender quotas on executive teams and increasing representation of marginalized groups in senior positions, many private sector actors are stepping up to show the world that corporate culture doesn’t have to be incompatible with equality. On the contrary, evidence shows that not only is equality imperative for strong, sustained economic growth, but it is better for the bottom line. Strong correlations between promoting women to the executive suite are linked with increases in profitability—studies have shown that the typical firm experiences a 15% increase in profitability when it goes from having no women in corporate leadership (C-suite, Board of Directors) to 30% representation of women.

As the Minister of Gender Equality and Diversity for France Elisabeth Moreno stated during the Forum, “Equality is a fight for justice but also an opportunity for enhancing performance.”

The implementation of gender-mainstreamed and equality-oriented frameworks is certainly a big challenge—but companies can make small changes in internal policies that can help to drive wider systemic change in this arena. Some organizational practices could include: committing to gender pay equity; ensuring resource allocation for gender-related training (gender sensitivity, positive masculinity, sexual harassment) on a regular basis with check-ins; developing the talent of women and BIPOC (confidence and other skills building courses, providing membership in mentorship programs); setting quotas for women and BIPOC in senior positions and on executive teams; and encouraging all employees to take caregiving leave (shifting the narrative particularly around men and caregiving).

Even though evidence makes a strong business case for equality, many private sector actors—especially in more traditional industries—need stronger incentives to foster organizational change and reform to align with the gender agenda. Governments, civil society, and especially consumers, can help drive corporations to adopt more equality-oriented principles, especially by engaging in dialogue across sectors, sharing best practices, and holding industries and their leaders accountable in a comprehensive way. Even though evidence makes a strong business case for equality, many private sector actors—especially in more traditional industries—need stronger incentives to foster organizational change and reform to align with the gender agenda. Governments, civil society, and especially consumers, can help drive corporations to adopt more equality-oriented principles, especially by engaging in dialogue across sectors, sharing best practices, and holding industries and their leaders accountable in a comprehensive way.

One way to do this would be for government, civil society and action coalition leaders to develop a gender-based criterion and framework for evaluating organizations on their alignment to gender mainstreaming values, not only on economic justice and rights, but on all issue areas. For instance, some companies may align with the gender agenda in some ways (such as CSR initiatives that prioritize girls’ education, or strong representation of women in their C-Suite), but may be violating equality-oriented principles in other ways (such as through the use of sweatshop labor, or the use of stolen land). This system of ‘grading’ actors could then be used to assess potential for partnerships, or used in determining eligibility for government grants, assistance, or stipends.

Another way to engender equality-oriented values could be through national legislation, as is the case of GEF Commitment-Maker, the Government of France under President Macron, where their National Assembly unanimously voted on a draft law on breakthrough measures on gender equity in May. These measures not only set gender quotas for leadership pipelines and investment committees, but also include actions to support women in broader ways, such as increasing women’s access to secure loans from a French public bank, and providing single-parent families headed by women with training and childcare.

France, and other GEF Commitment-Makers—from the Governments of Iceland and Norway to companies Unilever, Procter & Gamble and Paypal—are well placed to lead the way in initiating policy shifts to support the economic justice and rights for women and other marginalized groups. But they must be held accountable, through partnerships and public pressure, to remind them that investing in equality reaps profits for all.

Ainab Rahman is a gender and security practitioner, and a member of the WFPG. She currently serves as Director at a global strategic advisory and intelligence company.

First Image Copyright © Women's Foreign Policy Group 2021

Second Image Copyright © International Labor Organization 2021

Return to top

With keynote remarks by French President Emmanuel Macron, US Vice President Kamala Harris, former US Secretary of State Hilary Clinton and UN Women's Executive Director and former Deputy President of South Africa Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, the 2021's second Generation Equality Forum, held in Paris from June 30th - July 2nd, articulated the pressing need to continue fighting for gender equality, particularly in response to the challenges, exacerbated by the COVID19 pandemic, faced by women and other marginalized groups. The Forum, sponsored by UN Women, brought together governments, private companies and civil society, to not only continue making their multi-sectoral commitment to gender equality goals, but to demand their acceleration both across the West and the Global South.

The three-day conference featured a number of high-level leaders, including: the President of Kenya, who spoke about his country's efforts in developing technological tools for gender mainstreaming and gender data collection; the President of Iceland, who spoke about the need to hold men accountable for toxic masculinity and gender-based violence; and the French Minister for Gender Equality and Diversity, who spoke about the introduction of gender quotas for executive teams, leadership pipelines and investment teams. In her remarks in the Opening Ceremony, US Vice President Harris emphasized how a healthy democracy needs women's participation and representation to function. "When women are heard at the ballot box, and in the halls of government, democracy is more complete," she reinforced.

Along with raising $40 billion in funding for gender-related initiatives, the Forum witnessed a number of commitments from decision-makers across government and the private sector to accelerate the gender agenda and to support women's leadership. Some notable commitments included: Paypal, who will contribute more than 10,000 hours of skills capacity building to nonprofits working on gender data; Estee Lauder, who made a commitment to increase representation of marginalized groups and gender parity in senior positions by 2025; Procter & Gamble, who committed to spending $10 billion on woman-owned businesses; and Unilever, who made a commitment to mandate payment of fair living wages for all.

But by far, the most impactful voices were those of the young leaders. Julieta Martinez, 17-year old founder of the platform Tremendas who, sharing the stage with former US Secretary of State, Hilary Clinton during the Opening Ceremony, eloquently spoke of the invisible women who fight every day for social justice, and who feel forgotten and abandoned by the system. Touching on the theme of intersectionality, she also discussed climate justice, coining the now viral phrase "when women rise, CO2 levels fall."

24-year old Shudufhadzo Musida, Miss South Africa, advocated for the need to increase access to mental health care for women and girls, as a vital tool for collective development. She emphasized how mental health services support women and girls in building their identity and confidence, playing an important role in women's leadership, stating its necessity in "empowering girls and women so that we can change the narrative, so that we can get our own seat at the table." 24-year old Shudufhadzo Musida, Miss South Africa, advocated for the need to increase access to mental health care for women and girls, as a vital tool for collective development. She emphasized how mental health services support women and girls in building their identity and confidence, playing an important role in women's leadership, stating its necessity in "empowering girls and women so that we can change the narrative, so that we can get our own seat at the table."

An inspiring trans activist in another session eschewed the traditional idea of 'getting a seat at the table' altogether, instead bravely envisioning a world where democracy is defined as collectivizing outside of racist, colonial and formal political structures.

Charged with the determination and vigor of the new generation, the close of the Generation Equality Forum saw many decision-makers, activists, innovators and corporations make concrete commitments to accelerate the gender agenda. But most importantly, the conference centered the need to spotlight young leaders and their voices in driving intersectional change and revisioning a truly feminist future in the years to come. As one young leader energetically closed—"Now, we get to work!"

Ainab Rahman is a gender and security practitioner, and a member of the WFPG. She currently serves as Director at a global strategic advisory and intelligence company.

Photos: (1) World leaders at the Opening Ceremony of the Generation Equality Forum held in Paris, France from June 30 to July 2, 2021 (2) 17-year old Brazilian rapper MC Soffia also performed during one of the showcases, rapping about racism and beauty ideals. "Your hair is the crown of a queen, don't forget," she reminded the audience.

Return to top

It's been more than 25 years since the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action was adopted during the landmark Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995. Unfortunately, the promising public rhetoric of the Conference has not been matched by action and implementation, and not one country today can claim to have achieved gender equality. The Generation Equality Forum (GEF) is our once-in-a-decade opportunity to change that.

The GEF is an inflection point on gender equality, which will see governments, corporations, and change-makers rallying around a commitment to #ActForEqual at a critical moment for the world. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to expose and exacerbate gender inequality, the Forum offers an opportunity to advance women's rights and ensure that gender is at the center of the post-COVID agenda.

The Bold Feminist Agenda the World Needs

The historic gathering, convened by UN Women, is guided by a bold feminist agenda — exactly what the wold needs right now. With diverse voices at the table, it will launch concrete, ambitious, and transformative actions to achieve lasting progress toward gender equality. The Forum is a civil society-centered, global gathering focused on intergenerational and multistakeholder partnerships.

The Generation Equality process kicked off in Mexico City in March and will culminate in Paris from June 30 to July 2. It is organized through six Action Coalitions (ACs) — multistakeholder partnerships that are working to catalyze collective action, drive increased investments, and deliver concrete results for girls and women around the world. The coalitions are being led by governments, international organizations, the private sector, civil society, philanthropies, and youth-led organizations. Through negotiations for the past year, AC leaders have decided on a set of actions and tactics to address the most critical issues facing girls and women today, and to achieve real, lasting change.

The themes for the six Action Coalitions are:

1. Gender-based Violence

2. Economic Justice and Rights

3. Bodily Autonomy and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR)

4. Feminist Action for Climate Justice

5. Technology and Innovation for Gender Equality

6. Feminist Movements and Leadership

What Will Happen In Paris?

Over three days, the virtual gathering, co-hosted by the Government of France, will bring together heads of states and governments, representatives from civil society, women's rights organizations, philanthropic foundations, and the private sector. Commitment-makers will join Action Coalition leaders to announce their concrete and ambitious commitments toward achieving gender equality. The AC leaders are committed to the Generation Equality process for the next five years, though the commitments range from anywhere between one year and five years. Commitment-makers can decide to make a programmatic, financial, advocacy, or policy commitment — but it must be game-changing, measurable, and ideally designed with other stakeholders.

Paris will be a critical inflection point for gender equality, but it's only the beginning. The real work starts once the commitments have been launched and are being implemented and measured. To keep the momentum going, there will also be future opportunities for organizations to get involved in the Generation Equality Forum and become commitment-makers.

Register for the Generation Equality Forum in Paris

The Paris GEF will be virtual, free, and open to everyone. Registration is open here until June 29 at midnight CET.

Minna Penttila is the Generation Equality Engagement Grants Manager at the UN Foundation. Prior to joining the UN Foundation, Minna worked at the secretariat of the Freedom Online Coalition, a network of governments advancing Internet freedom and human rights online, and at the Ford Foundation, where she supported grantmaking in gender and reproductive justice, immigrant rights, racial justice and criminal justice reform.

This post originally appeared as a blog post on The United Nations Foundation.

Return to top