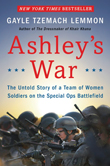

Ashley's War:

The Untold Story of a Team of Women Soldiers on the Special Ops Battlefield

Gayle Tzemach Lemmon, Council on Foreign Relations

Photos

Washington, DC—On July 21, 2015, Gayle Tzemach Lemmon, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, spoke at an Author Series event on her latest book, Ashley’s War: The Untold Story of a Team of Women Soldiers on the Special Ops Battlefield. During her talk, Lemmon shared the story of a group of women determined to prove themselves by participating in dangerous missions in Afghanistan during a time when women were officially excluded from ground combat positions. She described why US military leaders needed women on the ground, the formation of the cultural support teams (CST), and the program’s grueling selection process. In writing about Ashley White and other CST members, Lemmon wanted to shed light on what women have already accomplished rather than speculate on their capabilities and limitations, as well as raise awareness about the future of women in combat.

Lemmon discussed the factors that influenced the decision to include women on the battlefield in the post 9/11 wars. Lemmon described how it was considered culturally inappropriate for male US soldiers to engage directly with Afghan women, who were seen as an untapped source of valuable information on matters related to the Taliban insurgency; as a result of the inability to communicate with half the population, military leaders concluded that winning the war would be impossible without women. When the decision to recruit women was made in 2010, the combat ban was still officially in place, so the only way for women to serve with special operations forces to attach them to a unit. The name “cultural support team” was devised for the program: “culture” referred to the proposed interaction with Afghan women and “support” signified that this was not a “backdoor way to frontline operator positions.”

To recruit the cultural support teams, a poster was distributed to different military units calling for women who wished to be a part of history; in response, several hundred applications were submitted by women who had always wanted to serve in special operations. In May 2011, 200 applicants gathered at Camp Mackall for the selection process known as “100 Hours of Hell,” which was a series of grueling mental and physical tests designed to identify those with the ability to survive on the battlefield. 55 women were selected to join the CSTs, and about 20 of them were chosen to go on direct action missions with special operations forces. The team was comprised of women from all different backgrounds, including West Point graduates, military police officers, and war veterans. Ashley White, an ROTC graduate from Ohio, was among those chosen for direct action missions; she was also the first CST to be killed on a mission. Lemmon described her as a combination of “Martha Stewart and GI Jane,” a newlywed who loved to cook dinner for her husband and then put “45 or 50 pounds on her back and go march for eight or nine or ten miles.” Her strength and courage was inspiring to those who knew her, and she became the heart and soul of this group of women who started as teammates and ended as family.

The CSTs arrived in Afghanistan in August 2011, and those who had been selected for direct action missions accompanied special operations units on night raids. Their job was to clear the women’s quarters, and then work with an interpreter to question the women about the insurgency. They often obtained valuable information that would later save the special operations forces time or even lives. Lemmon stated that they constantly had to prove themselves as even one mistake would reflect poorly on all of the other CSTs. Despite the extra effort they had to put forth, Lemmon emphasized that these women delivered on mission each night, and they quickly became valuable members of the special operations team.

With the upcoming January 2016 deadline for full integration of women in the military, audience members were concerned about how the absence of unified public male support on this issue will affect future implementation. Lemmon stated that as the nature of warfare changes, new roles have been created that require women to fill them, especially as the battlefield has been brought to the doorstep. She compared the issue to gay marriage, meaning that the integration of women in combat is now considered a mainstream political issue as more people support full integration. She also cited the increased number of women in leadership roles, as well as generational shifts as two additional factors that have weakened the opposition on this issue.

Lemmon stressed that Ashley’s War is a story of strength, valor, and courage, yet she acknowledged the dangers women face in the military, including both high levels of sexual assault and PTSD. She cautioned, however, that by focusing too much on the hazards, “the victim story is now trumping everything else” surrounding women in combat. She added that so much of the current conversation has been dominated by what standards women could and should meet, and that very little attention has been given to the strides already made. Her goal in writing Ashley’s War was to “show the full breadth of what’s happening with women in combat” to highlight their often overlooked contributions in the post 9/11 wars. By focusing on their heroism, Lemmon was able to reconstruct an old-fashioned war story with characters that more closely reflect the current composition of the United States military.